Why Arallu Feels Alive

Arallu is the heart of my speculative fiction project, The Woven Edge.

“The seams of reality are thin, and every choice leaves a mark.”

Introducing Arallu

Arallu is the heart of my speculative fiction project, The Woven Edge. The name itself is borrowed from Mesopotamian myth, where Arallu referred to the land of the dead — an underworld of dust, silence, and shadows. In my story, that echo persists, but reshaped into something new: not an afterlife, but the fragile prime reality upon which all others rest.

When I say “Arallu,” I don’t just mean a place. It is the world itself — deserts, skies, weather systems, creatures, and people bound together in fragile equilibrium. It is both vast and intimate: a crossroads where politics, memory, and survival collide.

In the cosmology of The Woven Edge, Arallu exists at the axis of The Loom — the fabric of existence itself. Every other reality brushes against it, overlapping or reflecting here, and those intersections leave scars. Time can stutter. People can feel echoes of lives not lived. The weather itself might remember something that happened centuries ago. Arallu isn’t just a setting for the story — it’s the source of all realities, and it carries the weight of that paradox.

This first glimpse into Arallu isn’t meant to map every street or Kardo, it’s capital, or catalog every creature. Instead, it’s about why the place itself feels alive — not a backdrop for the story, but an active force shaping the trilogy.

More Than a Location

When I talk about Arallu, I don’t just mean the metropolis, Kardo, at its center. Arallu is its deserts, skies, fauna, and weather.

- The deserts act as both barrier and lifeline: stretches of deadly emptiness cut with fertile oases where whole communities cling to survival.

- The skies ripple with instability, almost as if resonance itself leaks into the atmosphere. Colors and patterns arrive like storms, transforming the horizon into something uncanny.

- The fauna evolve strangely, shaped by a world that resists stasis. Their forms sometimes mirror the instability of the land - creatures that are half-familiar, half-other.

- The weather remembers. Storms roll in not randomly, but in recurring patterns, like scars replaying themselves across time.

Together, these elements make Arallu feel less like a setting and more like a living ecosystem of instability.

Layers of Memory: Mesopotamian Roots

The inspiration for Arallu’s architecture draws heavily from the ancient Mesopotamian ziggurat. These stepped temples weren’t just buildings; they were symbols of order in the midst of chaos. Rising from mudbrick foundations that constantly crumbled and were rebuilt, ziggurats became palimpsests of memory - each layer recording both construction and decay.

That idea fed directly into Kardo’s design. The city grows upward and outward, but never cleanly. New structures are built atop the old, not erasing but incorporating them. The effect is one of living memory. You can’t walk its streets without feeling the weight of what came before.

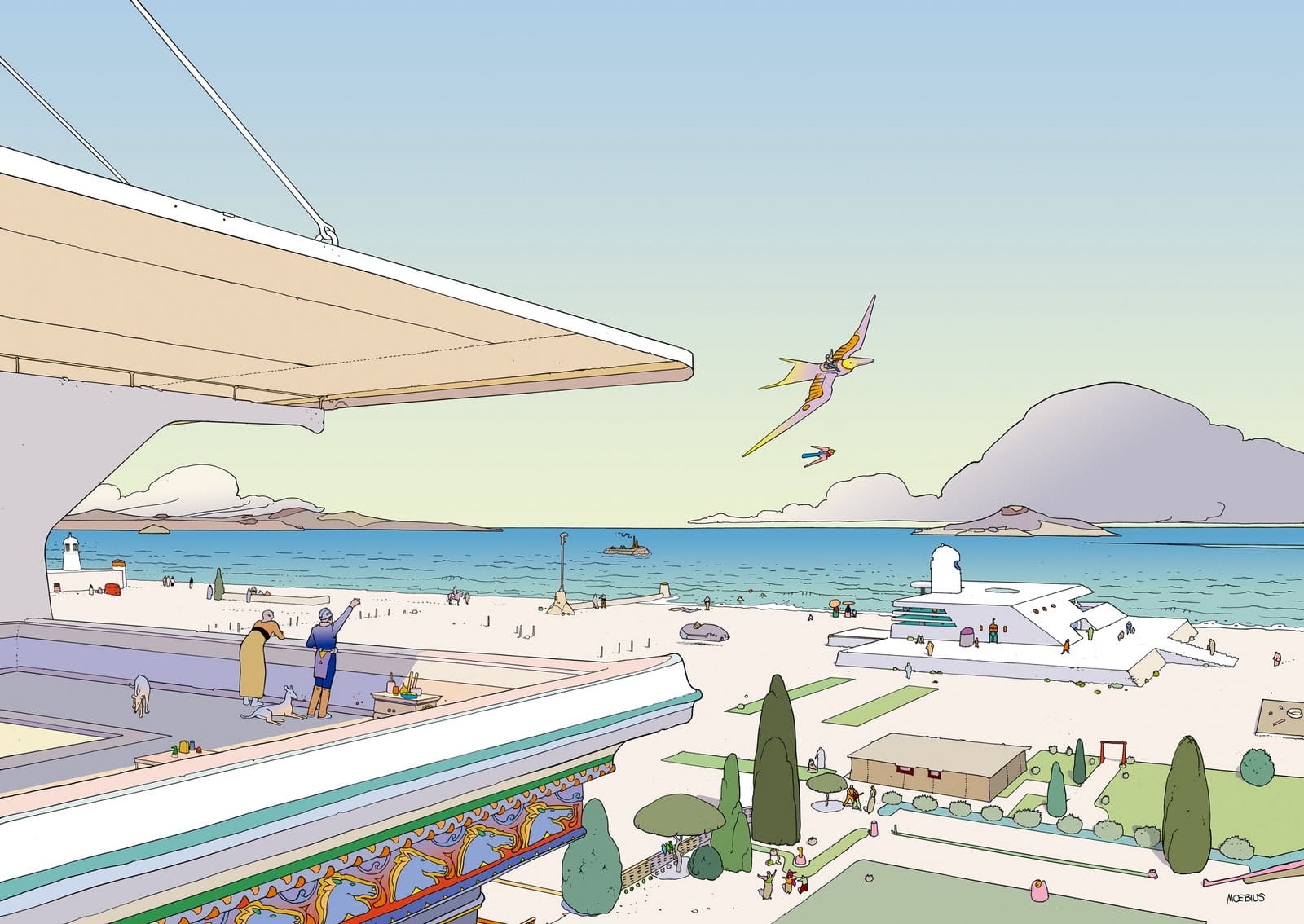

Moebius and the Surreal Aesthetic

Visually, Arallu owes a debt to Jean “Moebius” Giraud, whose work reshaped how we imagine alien worlds. His art fused crisp geometry with dream logic: towers that stretch into infinity, deserts that pulse with strange color, skies that refuse to settle into blue.

Moebius’ worlds feel uncanny because they are at once deeply detailed and impossibly surreal. That tension was exactly what I wanted for Arallu.

The result: a world that feels at once ancient and alien, grounded in the material textures of Mesopotamian architecture, but filtered through the strange elegance of Moebius’ line work.

Why Arallu Feels Alive

Arallu is a city, a desert, a storm system, a sky, a memory. It doesn’t wait politely in the background—it acts. Its shifts change the fate of characters. Its instability drives politics and faith. Its resonance leaves scars on people just as surely as on the land.

That’s what makes Arallu feel alive: it refuses to be static.

Looking Ahead

This post is part of a series exploring the world-building of The Woven Edge, my in-progress speculative fiction novel — book one of a planned trilogy.

Next time, we’ll move from the surreal landscape to the bureaucratic halls of Kardo, where world-building doesn’t just happen in stone or sand, but in systems of control.

Want the next world-building update delivered to you?

Join the free Observer tier and get posts, notes, and behind-the-scenes updates as The Woven Edge takes shape.